Continued from Part 1.

The true nature and identity of Tom Bombadil is a mystery even to scholars and fans of The Lord of the Rings. Some have suggested that he is one of the Valar, the Powers of the World, the rulers who were sent to Eä (the universe) by Eru Ilúvatar. Possibly so. It’s clear that the jolly, silly, carefree Tom Bombadil persona serves to disguise a deeper, wiser, more powerful reality than Tom lets on. Tolkien isn’t telling, and we can never know for sure.

Tolkien in 1916

We do know that Tom’s stature as a mythic figure grew in the telling. Tolkien originally conceived Tom Bombadil as a having a smaller role and lesser significance in a planned sequel to The Hobbit—the role of a mere forest sprite or spirit. In a 1937 letter, Tolkien pondered whether “Tom Bombadil, the spirit of the (vanishing) Oxford and Berkshire countryside, could be made into the hero of a story.” As Tolkien’s vision for The Lord of the Rings grew, so did the stature—and mystery—of Tom Bombadil.

As filmmaker Peter Jackson demonstrated, you can advance the storyline of Tolkien’s tale quite economically by leaving Tom out. But in doing so, you lose something that is very important to the tale—and to Tolkien. As Tolkien himself wrote in a 1954 letter, Tom Bombadil “represents something that I feel important.” I believe Tom represents an elusive but crucial piece of Tolkien’s Christian worldview.My purpose here is not to pin down Tom Bombadil’s precise identity in Tolkien’s legendarium. Instead, I want to talk about Tom Bombadil’s unique place in Tolkien’s spiritual vision. The worldview, structure, and themes of The Lord of the Rings are drenched in Christian memes. So here is my theory about Tom:I believe Tom Bombadil represents the Holy Spirit, the Third Person of the Trinity in Christian belief. If Eru Ilúvatar, “The One, the Father of All,” is an echo of God the Father, and if Gandalf, Frodo and Strider are echoes of Christ as Prophet, Priest, and King, then there must be, embedded in The Lord of the Rings, an echo of the Holy Spirit’s influence.

Like the Holy Spirit, Tom possesses an irresistible power and authority, including authority over the created order (see Genesis 1:2). Tom brings comfort and wise counsel to the hobbits, much as the Holy Spirit, our all-wise Comforter who speaks healing to our souls (John 14:26). The Spirit calms our fears and brings us joy and peace. He refreshes us when we feel exhausted, gives us sound guidance and advice, and reminds us to avoid evil. These are all ministries that Tom performed among the hobbits.

The Spirit is God, so He is rightfully the Eldest, who was here before all things. The Spirit knew the dark under the stars before fear came into the world. The Spirit knows all things before they come to pass. Nothing catches the Spirit by surprise. We can conceal nothing from the Spirit, and sin (like the Ring) is no match for the power of the Spirit. We can’t hide from the Spirit, and He rescues us when we call to Him.

Perhaps the most important parallel is this: The Holy Spirit gives us gifts. Tom Bombadil echoes the Spirit by giving gifts to the hobbits. Tom gives them ponies, and he also gives them daggers from the Barrow-wights’ treasure horde. The daggers have blades that “seemed untouched by time, unrusted, sharp, glittering in the sun.” The daggers are swords for the hobbits to use for self-defense on their journey. “Old knives are long enough as swords for hobbit-people,” Tom tells them. “Sharp blades are good to have.”

Clearly, the hobbits don’t fully appreciate the true nature of the battle they have joined. Tolkien writes, “Fighting had not before occurred to any of them as one of the adventures in which their flight would land them.” This echoes our own obliviousness to the spiritual battle of this life. As Paul writes, “For our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms” (Ephesians 6:12 NIV).

And how does the Holy Spirit arm us for spiritual warfare? The same way Tom Bombadil armed the hobbits: with a sword. Paul writes: “Take the helmet of salvation and the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God” (Ephesians 6:17 NIV). And Hebrews 4:12 also compares God’s Word to a sword: “For the word of God is alive and active. Sharper than any double-edged sword, it penetrates even to dividing soul and spirit, joints and marrow; it judges the thoughts and attitudes of the heart.”

Tom’s gift of the ponies enables the hobbits to carry out their mission more effectively. The ponies remind us of the gifts of ministry that the Spirit gives to believers, as described in Romans 12, 1 Corinthians 12, Ephesians 4, and elsewhere.

The God-likeness of Tom Bombadil is reinforced by Goldberry. When Frodo asks her, “Tell me, if my asking does not seem foolish, who is Tom Bombadil?,” she replies simply, “He is.” That is clearly a parallel to God’s own statement about himself, “I Am that I Am” (see Exodus 3:14).

In all of these ways, Tom Bombadil is an echo of the Holy Spirit. Is Tom an allegory of the Holy Spirit? No. Tolkien disliked and distrusted allegory. Symbolic characters in The Lord of the Rings offer a resonance of a deeper reality, but they are not intended to teach Bunyanesque lessons.

At the Council of Elrond, we hear many things about Tom Bombadil that are both like and unlike the ministry of the Spirit. Like the Spirit, Tom has set the boundaries of his realm and will not step over them. The Spirit is a still, small voice who invites us to follow Christ—but the Spirit respects human free will and will not step over that boundary.

House at 20 Northmoor Road, Oxford, England, where Tolkien wrote The Lord of the Rings

But at the Council there are things said about Tom that directly contradict the idea that he is a symbolic echo of the Spirit. First, Gandalf says that Tom would be “a most unsafe guardian” of the Ring, and “would soon forget it, or most likely throw it away.” That certainly doesn’t sound like the Spirit! Second, the elf Glorfindel says that Tom would ultimately fall to the onslaught of the Enemy—”Last as he was First; and then Night will come.” Clearly, the Holy Spirit could never be overcome by the evil of the Enemy.

So these descriptions of Tom at the Council of Elrond seem to undermine my theory that Tom represents the Holy Spirit. I see two possible explanations for this contradiction:

1. In Tolkien’s mind, Gandalf and Glorfindel might simply have been wrong about Tom. They might not have recognized the true depths of Tom Bombadil’s power and wisdom. But I think this explanation is unlikely. It’s hard to imagine that Gandalf could have misread Tom so completely. I think the likelier explanation is:

2. Here is where the similarities between Tom and the Holy Spirit end. Tom is not an allegorical figure. He echoes some aspects of the Spirit—but not all. At some point, the analogy must fail. Tom is a character of fiction after all. Tolkien didn’t intend to teach us about God through Tom and the other God-like characters. He intended to connect with something we already know about God, so that these characters would have greater depth and resonance than mere words on a page. He was tapping into our consciousness of God.

I’m not sure that Tolkien consciously and deliberately created Tom with all of these echoes and resonances of the Holy Spirit. Some of these symbolic parallels may have originated in a subconscious act of the author’s creativity and imagination, infused by his faith. In The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien, the author wrote that Tom Bombadil “represents something that I feel important, though I would not be prepared to analyse the feeling precisely. . . . Even in a mythical age there must be some enigmas, as there always are. Tom Bombadil is one (intentionally).”

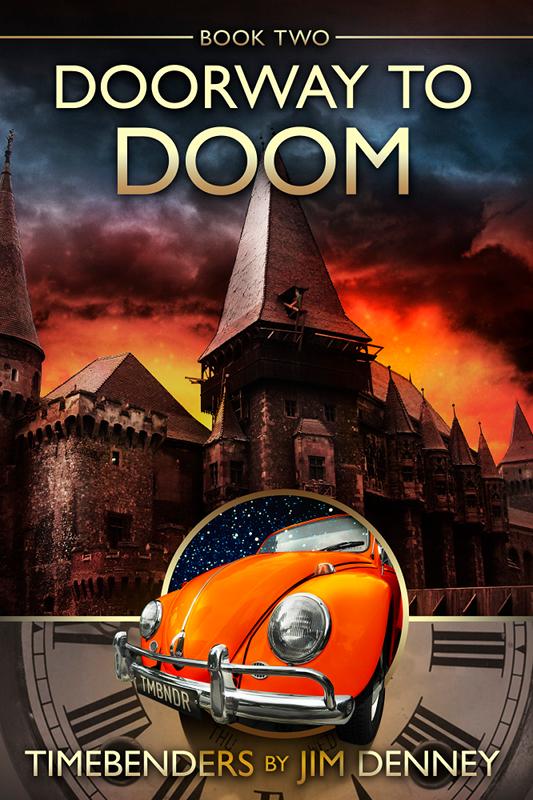

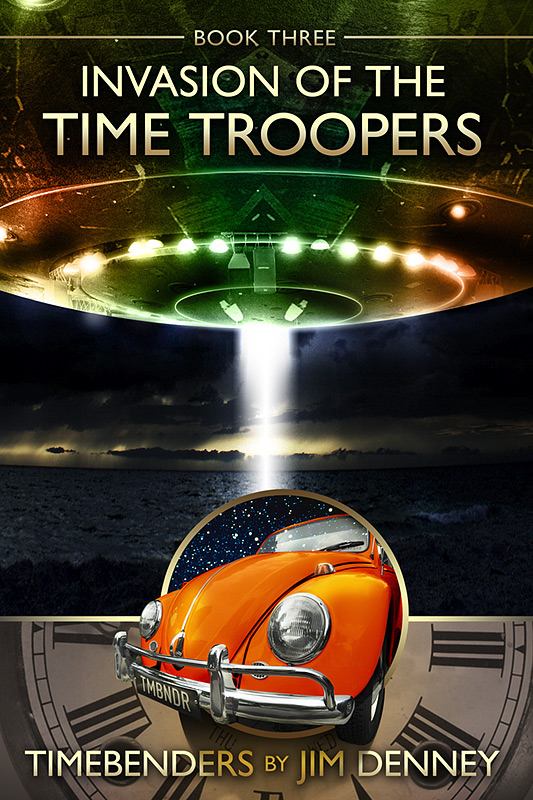

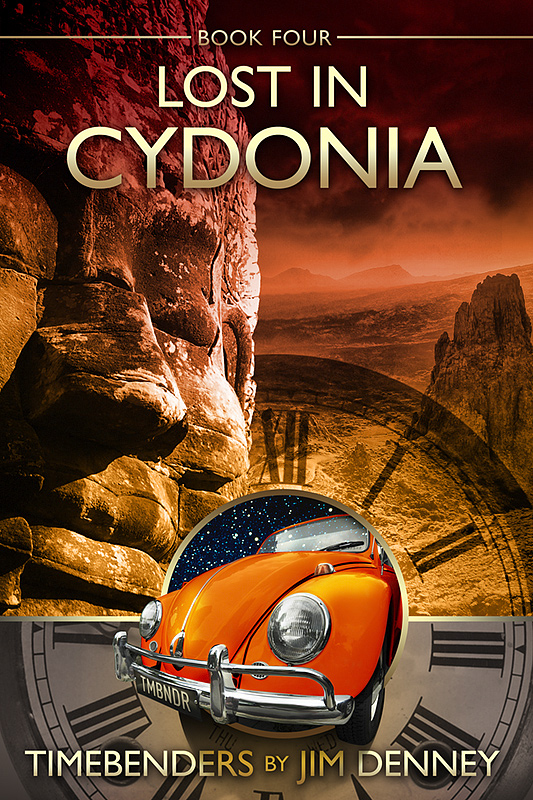

As I was writing my Timebenders series (beginning with Battle Before Time), I often discovered spiritual symbols and parallels in the work only after I had written it. I didn’t always consciously intend for this event or that character to stand for something larger. But later—sometimes years later—I would reread the story and discover what my subconscious imagination had been up to while hiding from my conscious intellect. I’m sure Tolkien must have had similar experiences again and again.

I was very impressed with the Peter Jackson film version of The Lord of the Rings—but I did miss Tom Bombadil. The enigma of Tom Bombadil is a crucial dimension of Tolkien’s original story. Tom gives us a glimpse into the underlying spiritual reality of the War of the Ring. Without Tom, without that still small voice of the Spirit infusing the earth and air and water of Middle Earth, something doesn’t quite ring true.

Much of the power of Tolkien’s story comes from the fact that it feels like it is also our story—the story of spiritual warfare in the real world, the story of a struggle that is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, authorities, and powers of this dark world, and against the forces of evil in the heavenly realms. The enigmatic Tom Bombadil is an irreplaceable part of The Lord of the Rings. Tom visibly represents that invisible Presence, the Holy Spirit, whose still, small voice speaks softly to us throughout the tale, and throughout our lives.